Under Vulture-less skies

2 August 2016 | The Mara | Duncan Butchart

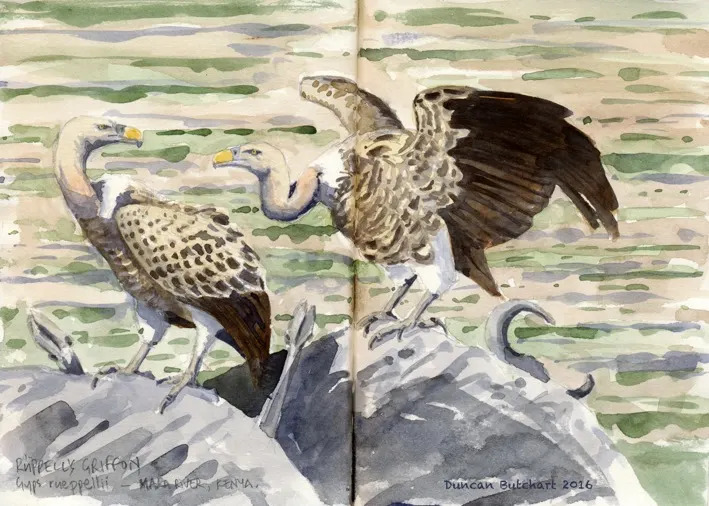

[Watercolour illustration by Duncan Butchart of two Ruppell’s Griffons feeding on bloated wildebeest carcasses in the Mara River ]

Everyone knows that vultures are scavengers, feeding on the dead, but one of the things that mystifies many people, is how so many vultures can arrive, so suddenly, at the motionless carcass of a wildebeest or zebra that might have lay undiscovered for hours.

African vultures do not have a sense of smell (unlike the Turkey and Black Vultures of the Americas, and carrion-seeking flies) – they rely entirely on their eyesight to locate their meals.

In the Mara-Serengeti, vultures basically fall into two groups: the heavy-bodied ‘griffons’ that aggregate in large numbers and bolt down chunks of flesh, and the more aerially agile and lightweight vultures that usually feed on the fringe of an unruly mob, picking away at skin and sinew.

The way in which vultures and other large scavenging birds find food is simply to get up into the air. The higher you get the more you see, and the heavy griffons, weighing up to 9 kg, have to get into thermals (rising columns of air) in order to stay airborne. High over the Mara-Serengeti, often above 1,200 metres and invisible to the human eye, griffons are looking down, not for inert carcasses which would not show up even to their sharp eyes at that distance, but for the movement of other vultures, below them.

White-headed and Hooded Vultures usually soar at an altitude of between 80 and 200 metres above the ground, where it is easy to spot a dead wildebeest. As they then drop height and swoop in, they are seen by the birds above them, and the birds above them, and so on. Now we have a sort of network, an invisible ‘net’ pulling vultures in from far and wide. It is as if a message has been sent outwards in all directions, and indeed it has. It has been calculated that vultures within a distance of at least 35km can be pulled in to a single source, so a dead wildebeest in the Mara Triangle might lure in a bird that is soaring a kilometre above Lobo Kopies in the Serengeti, or the Mara Conservancies near Aitong. This is probably a very conservative suggestion, and the ‘net’ could easily be wider.

The pattern of arrival is also interesting, there may be just a few vultures feeding for an hour after the ‘discovery’ and then, perhaps, 200 arrive within the next 20 minutes. Such an event indicates that vultures were pulled in from a hitherto ‘empty’ part of the sky.

Naturally, perhaps, most people on safari don’t find gangs of bloody vultures feeding on gore very appealing and they quickly move on. This is a shame, because these superbly adapted birds are not only interesting to watch and photograph, but their ecological role is vital to the health of the Mara-Serengeti, and to all other wildlife areas in Africa.

Research by David Houston in the Serengeti showed that only 14 % of carcasses fed upon by vultures (in a 12 week study period from January to March) were originally predator kills – almost everything the vultures consumed was a ‘natural mortality’. When you consider that over a million wildebeest are born on the short-grass plains of the Serengeti every year, and that over 60% of these calves are estimated to die within their first year, it is plain to see that vultures do not rely on lions or cheetahs. And this is just the young wildebeest, many adults die on route and there are of course zebras, gazelles and buffalo, none of which live forever. At any rate, since the big cats and hyenas leave precious little of their meals, the vultures could never depend on them for sustenance.

Suffice to say that a savanna landscape without vultures to remove the dead would be a messy, disease-ridden place. Epidemics of anthrax, botulism and who knows what else could decimate herbivore populations, and the predators would follow. Most disturbingly, this dreadful and bleak scenario now threatens across Africa.

The remarkable foraging technique described above is the very thing that makes vultures so vulnerable. Elephant and rhino poaching gangs now lace carcasses (removed of their tusks and horns) with poisons for the express purpose of killing vultures. They do this to eliminate these birds which otherwise act as highly effective alerts for anti-poaching teams intent on tracking their whereabouts. Secondary poisoning, where vultures feed on carcasses of lions, hyenas and other predators thought guilty of livestock predation and killed with poison bait, claims an equally large number of vultures, and then there is the direct killing of vultures for their supposed role in traditional medicine. Again, for their remarkable powers of detection, mystics believe that vultures are able to see into the future and so their bones and dried brains are in demand as supernatural tools to predict outcomes of elections, football matches or whether an unborn child might be a girl or boy.

Due to this rampant use of readily available poisons, virtually all of Africa’s vulture species are now classified as ‘endangered’ or ‘critically endangered’ in the IUCN’s ‘Red Data Book’. BirdLife International and other conservation agencies are now intent on finding solutions to this tragic and very difficult to combat situation.

Note from the Editor: Duncan Butchart is also the co-author and illustrator of The Vultures of Africa – a tome published in 1992 by Academic Press (London & New York) – now out of print and a valued collectors’ item.

COMMENTS (2)

yvonne yohe

August 2, 2016Interesting read! Thank you, Duncan.

REPLYAlison

August 3, 2016Fascinating and absolutely tragic to hear how these birds are being eradicated. Thank you for this article!

REPLY