Behind the Closed Doors of Segera’s Explorer Lounge

14 April 2016 | East Africa Travel | Michael Boyd

I step into the past. Out of the dry, hot sun of Laikipia in northern Kenya, the room is cool and smells of old libraries and worn leather. In the middle of the room sits a snug set of sofas, surrounded by tables, display cabinets and bookcases littered with old suitcases, chests, maps, parchments, picture frames and other museum-worthy items. I feel like I have stepped into an Africa of the 1930s.

Segera’s Explorer Lounge sits on the second level of the Old Paddock building, just outside the luxury retreat. It overlooks the Star Deck, where at night an open fire burns and dawas await the return of safari-trekking guests. This is also where guest’s cars or aeroplanes pull in, to be met by the waving Segera team; their big smiles welcomed my wife Kate and I after a long but beautiful drive from Nairobi, skirting the base of Mount Kenya. The mountain rises from the horizon behind me, as I shut the door to the lounge.

I had been told that Segera is a home to arts, history and culture, as well as being an oasis amidst the wildlife on the Laikipia plateau – home to Kenya’s second-largest animal population (the Maasai Mara takes gold). Art is certainly a large part of the experience – not only is there a gallery of exquisite and thought-provoking contemporary African art, but the beautiful gardens are dotted with sculptures of the same. Being an English teacher, however, I was most looking forward to Segera’s literary aspect, and what the Explorer Lounge had to offer.

I am immediately attracted to an original poster of the film Out of Africa – still with drawing-pin holes and folds from its days on a cinema wall in 1985 – showing Meryl and Robert at the classic picnic scene (where Angama Mara sits today). Below the poster, I inspect an aeroplane engine, beautifully mounted. This is a piece of film history: the engine from the 1929-model gypsy moth biplane used in the other classic scene from Out of Africa – Meryl and Robert flying over the African plains, winning the film best cinematography that year. Segera is in fact home to the biplane from the film, which can be viewed in a hangar on the grounds.

This is not the only piece of Out of Africa here, however, as I spy classic photographs of the book’s author Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen) around the room. Today, Blixen is an old-world icon of Kenya. Here she bravely, but unsuccessfully, tried to farm coffee on a hard continent, with which she fell in love. In many ways this room reminds me of her home in Nairobi.

Other photographs fill bookshelves and side-tables. I see an old picture of a hunter, smiling proudly over his leopard kill. It suddenly clicks who it is! Ernest Hemingway, the (probably self-proclaimed) Great White Hunter himself. Hemingway made two trips to Africa in his life-time, once with his first wife and finally with his fourth wife – going on many classic safaris of yesteryear – and inspiring some of his greatest writing: the novel, The Green Hills of Africa, and his short stories The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Short and Happy Life of Francis Macomber (interestingly, both made into films starring Gregory Peck).

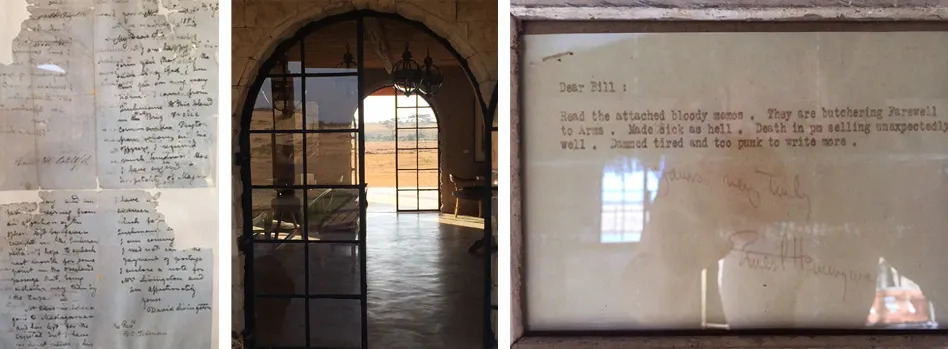

Photographs are not enough for this space, and I am happily surprised to find frames boasting original letters and telegrams from Hemingway, who died in in 1961; his classic signature uneven, scrawled in pencil across the page.

Other framed letters stand around the sofas. I sit and try to decipher the handwriting on one. Perhaps the best known of Africa’s explorers springs to life before me. David Livingstone traversed the continent surviving lion attacks and malaria, and was a missionary and explorer who was the first European to lay eyes upon – and name – the wonder of Victoria Falls. Like Hemingway, he also published a book – his diaries of his travels in Africa. Unfortunately, the book has not stood the test of time but is still available on Amazon. However, his achievements in the exploration of Africa are the stuff of great legend, and studies are still made of his extraordinary life (see here). While his body lies in Westminster Abbey, his heart is buried in Africa.

I open the door and step back in the heat of the afternoon sun. Mount Kenya stands majestically in front of me. I scan the grasslands and I am reminded that although I have just witnessed a version of African literature and history, it also surrounds me now. I think of my guide David, who explained to me the history of the name Segera, how it is the Maasai word for the cowrie shell – such a prized item, and form of currency many years ago. I asked him why this place would be so named?

Hundreds of years ago, two factions of the Maasai tribe – one from the north, the other from the south – clashed in a great war to win the perfect cattle land surrounding Mount Kenya. The two tribes fought viciously, David tells me, and many men died. After each battle, the Maasai elders would gather to count the dead. The precious cowrie shells were used to do so – each represented the life of a warrior. That took place upon this land: thus, Segera.

As David told me this, I was reminded that I live on a continent where literature is not only written. I was witnessing a piece of oral storytelling literature.

Behind me and around me is Africa’s past in literature and storytelling, but it is not the only one. Before me – on the other side of Mount Kenya, in Nairobi – lies Kenya’s written future, currently making history: Thiongo Wa Ngugi (A Grain of Wheat) and Binyavanga Wainaina (How to Write About Africa, One Day I Will Write About This Place) pave the way for other Kenyan writers.

The Explorer Lounge pays homage to some of the great characters of colonial Africa and is aptly named in this way. Indeed, I realise, the room is a testament to Africa as a muse – her inspiration translated and reflected into various writings, films and photographs. Here, colonial Africa comes to life vividly, neatly in unison with the stories of the land and the art of contemporary Africa in the gallery, not two minutes away. Segera boasts the best of both, and much more.

TAGGED WITH: Out of Africa, Arts and Crafts, Laikipia, Segera Retreat, North of Angama

COMMENTS (1)

Jane Hodges

April 20, 2016Loved hearing Mike’s ‘voice’ and was enthralled even before I realised who the author was! Amazing photographs! Esp of them two!

REPLY