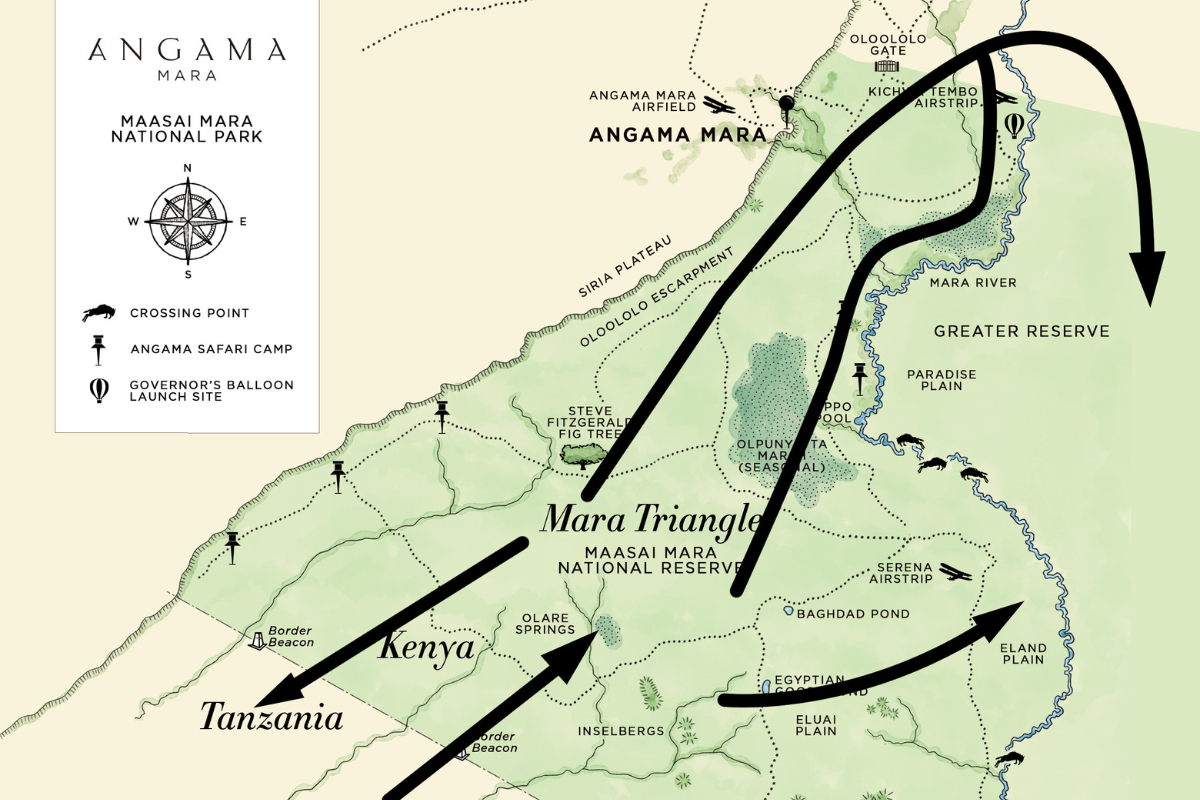

As the wind shifts, so does its influence on The Great Migration. This year, the seasonal rain patterns across the Serengeti and Maasai Mara have altered the movements of the wildebeest and zebra herds. Unlike previous years, some groups have now crossed into the Greater Mara through the northernmost points of the Triangle, while others have spread out towards the Topi and Eland plains, taking advantage of the new growth. Meanwhile, with the visible onset of rains to the south in the Serengeti, large numbers of animals are moving back and forth between Kenya and Tanzania, drawn by the promise of fresh grazing.

For several years, the Mara River crossings have been absent at the point just below Kichwa Tembo Airstrip. But now, with the herds having pushed further north into the Triangle, it was inevitable that they would have to cross this perilous section of the river at the Triangle's edge. For days, from Angama’s deck, we watched the dotted land below us, eagerly awaiting a river crossing. Nearby, the Nomad male lion, and not far from him, a female from the River Pride, were feasting in this season of abundance.

The search for fresh grazing and water, as well as the pressure of the herd, eventually became overwhelming, forcing them to attempt the dangerous river crossing. For three consecutive mornings, guests in the Triangle watched as the animals approached one of the river’s most treacherous points and hesitated, eyes fixed on the swift currents and jagged rocks ahead. But the surge of the thousands behind forced the leaders to plunge forward. Hooves slipped on moss-covered stones as chaos erupted — water splashed wildly, and the herd scrambled desperately to reach the other side. Occasionally, a wildebeest stumbled between rocks, risking being swept into the deeper, unforgiving waters.

For some, the danger is overwhelming, and fear takes over as the threat of being taken downstream grows imminent. Rather than face the swift current, some turn around in a frantic attempt to retreat, heading back to the safety of the riverbank. Crossing this rocky section of the river is a challenge that these animals must navigate carefully or risk injury. For those who successfully make it across, the reward is safety, but for others, the river’s dangers claim their lives.

At other crossing points, the drama is just as intense, with wildebeest making daring leaps into the river. The U-Point crossing recently witnessed one of the most crowded crossings of the season, where dust filled the air as hundreds of wildebeest made their frantic dash across the Mara River. Each leap felt more precarious than the last, creating a thrilling spectacle for those watching from the riverbank.

Spotting new lion cubs in the savannah is always a moment of pure excitement. We encountered a lioness from Maji Machafu pride, with her two new playful bundles of joy eagerly trying to keep up with their protective mother.

Not far from the lioness with her cubs, we encountered the dominant Inselbergs males, who reign over this territory. The trio — Manywele, Nusu, and Ruka — were resting after a satisfying feast, though their unmistakable 4th companion, Ginger, was notably absent. As the season of abundance continues, the lions are taking full advantage of the plentiful prey.

Ostrich chicks hatch from some of the largest eggs in the animal kingdom, yet the size relative to the adult bird is surprisingly the smallest. These fluffy, light-brown chicks are well-adapted to their environment from birth and can walk and run just hours after hatching. They are incredibly resilient and grow rapidly, gaining around one foot in height every month. Despite their small size at birth, they stay close to the adults in their group, who fiercely protect them from predators. Ostrich parents are known to be highly protective, often working together to shield and care for their brood, ensuring the survival of the next generation of these flightless giants. –Robert Sayialel

This week will be my last writing for TWAA after almost three years at Angama. I have developed a deep appreciation for the wild and specific animals and ecosystems — the Mara and Amboseli hold a permanent place in my heart. With just a week left in Kimana, I’m savouring every second. Whether a grand spectacle or a quiet moment, each sighting feels special.

At its most fundamental level, the universe can be described as a vibration or wave, encompassing matter, energy and even consciousness. Reminding us that we are not separate from nature but an integral part of it, connected to everything and everyone around us. When able to connect with nature and wildlife, you can feel the euphoric feeling that you are on the same frequency. I see the guides tune into this frequency, keenly observing animal behaviour, sounds, scents, tracks and even changes in the weather. I've also noticed guests develop a deeper connection to nature in these moments.

Large numbers of herbivores are gathering around the lodge because lions are in the area, and the animals feel safe near people. We’ve heard lions roaring in the dark of night several times this week. One morning, Osunash and Memusi were found within minutes of driving. They lay beside each other, and after some time, they got up and mated, indicating that she was not yet pregnant. We have seen them mate in the past but have not yet seen any cubs. Unfortunately, there is a chance that Memusi might have had the cubs, and they did not survive. Osunash looks like he was in a recent altercation with another male, probably 263. There was a large cut under his right eye. I informed Lion Guardians who will decide whether any intervention is necessary.

The Marshes of Amboseli are a vital ecosystem within the National Park. These wetlands are crucial for supporting diverse wildlife, especially during the dry season when other water sources may be scarce. The marshes are fed by underground springs from Mt. Kilimanjaro and surface runoff, providing a steady water supply for both animals and plants.

They also support a variety of aquatic plants, such as papyrus, reeds, and lilies, which serve as both food and shelter for wildlife. The marshes are big enough to support a wide range of animals, especially elephants, hippos, buffalos, and numerous bird species. As our guest Cenk Ozodogan found out, the water also creates unique photo opportunities.

On a sunrise drive, something suddenly darted through the grass — a creature the Swahili call 'sungura'. The African savannah hares are typically solitary and not seen during the day. They rely on camouflage to hide but can sprint at an impressive 70 km per hour, their zig-zag running pattern helping compensate for their limited ability to see directly in front of them. With a keen sense of smell, they can detect prey and predators as they move through the tall grass. Their large ears not only help with hearing but also regulate body temperature. To warn other hares, they often drum with their forelegs. Interestingly, in some local cultures, they are associated with music and drums.

The black-winged kite features a slender build, long wings, and striking black-and-white plumage, which you can spot in this area. Its name is derived from its distinctive black wings, although it was previously known as the 'white-tailed kite' or simply the 'kite'. The specific reason for the name change is unclear, but it is likely due to increased focus on the black wings as ornithologists and birdwatchers studied this species in more detail.

Drongos are often perched on treetops in Kimana, their long tails swaying in the breeze. They are highly intelligent birds, known to engage in various behaviours, such as mobbing predators, stealing food from other birds, and even mimicking human sounds. Their ability to mimic other birds' calls is particularly impressive, as they can accurately reproduce the sounds of various species, including hawks, owls, and crows. This mimicry serves several purposes, including deterring predators, attracting mates, and communicating with other drongos.

The African striped skink, also found around the Sanctuary, is a marvel of adaptation. Its slender body with striking stripes allows it to blend seamlessly into the surrounding vegetation. A master of camouflage, this agile reptile spends its days hunting for insects and other small invertebrates. When threatened, it employs a clever defence mechanism, shedding its tail to distract predators while it makes a swift escape. This remarkable ability, along with its speed and agility, ensures its survival in the often harsh and unpredictable African wilderness.

One of the intriguing aspects of the African mourning dove is that many people mistakenly associate its name with ‘morning’ due to its call often being heard at sunrise. In fact, its mournful 'coo' gives the bird its name, a sound people have linked to sadness and loss for centuries. These doves can be found throughout the Sanctuary, their plaintive calls echoing in the early hours.

Thank you for allowing me to express my love for nature through photos and words. It has been a privilege to share stories of the natural world with an audience that cares deeply about them. –Andrew Andrawes

Filed under: This Week at Angama

Subscribe for Weekly Stories

Comments (0):

Weddings in the Mara