After my first albeit humble publishing success I penned two other books but neither saw the light of day. I misplaced one manuscript while the other turned out a waffle.

During my second year at Kenyatta University, the writing bug bit again. I remember once skipping a maths class to finish an interesting story.

Two years later, I authored a collection of three stories and submitted the manuscript to a publisher. But this earned me a rejection slip. ‘Although the stories have minimal grammatical mistakes, they lacked literary flair which makes them unsuitable for publishing,’ came the rejoinder. That dampened my spirits a little, but I was also grateful for the brutally honest rebuttal. At any rate, I had met budding writers who sent their works to publishers but never received any feedback.

What with my passion for letters, the failure of my experimentations with the prose genre of literature only gave me more reason to read more of Cyprian Ekwensi, Henry Ole Kulet and others whose writing fascinated me. A number of prolific African authors are famous but less financially stable. Many live from hand to mouth like the late Dambudzo Marechera of Zimbabwe, author of the House of Hunger fame, who slept rough while his works sold like hot cakes. This might partly be attributed to the capitalistic nature of the publishing industry the world over. Save for self-publishers, a Kenyan author gets 10 percent per book sold while the publisher bags the rest.

Of course people write literary works for many reasons and not only necessarily to sell the product. Others want fame while yet others want to satirize ills in the world.

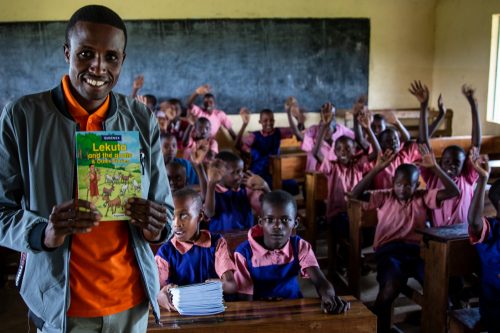

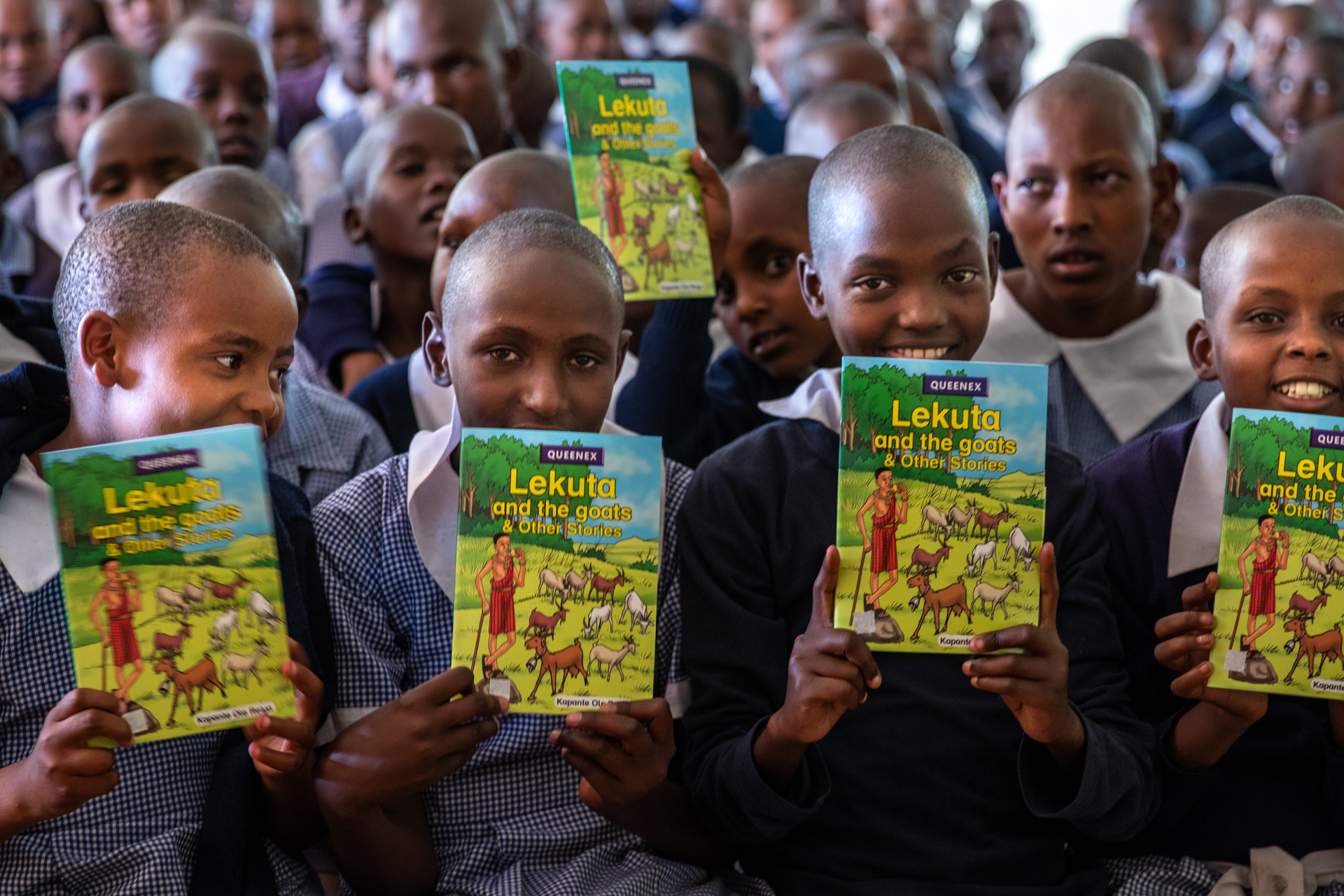

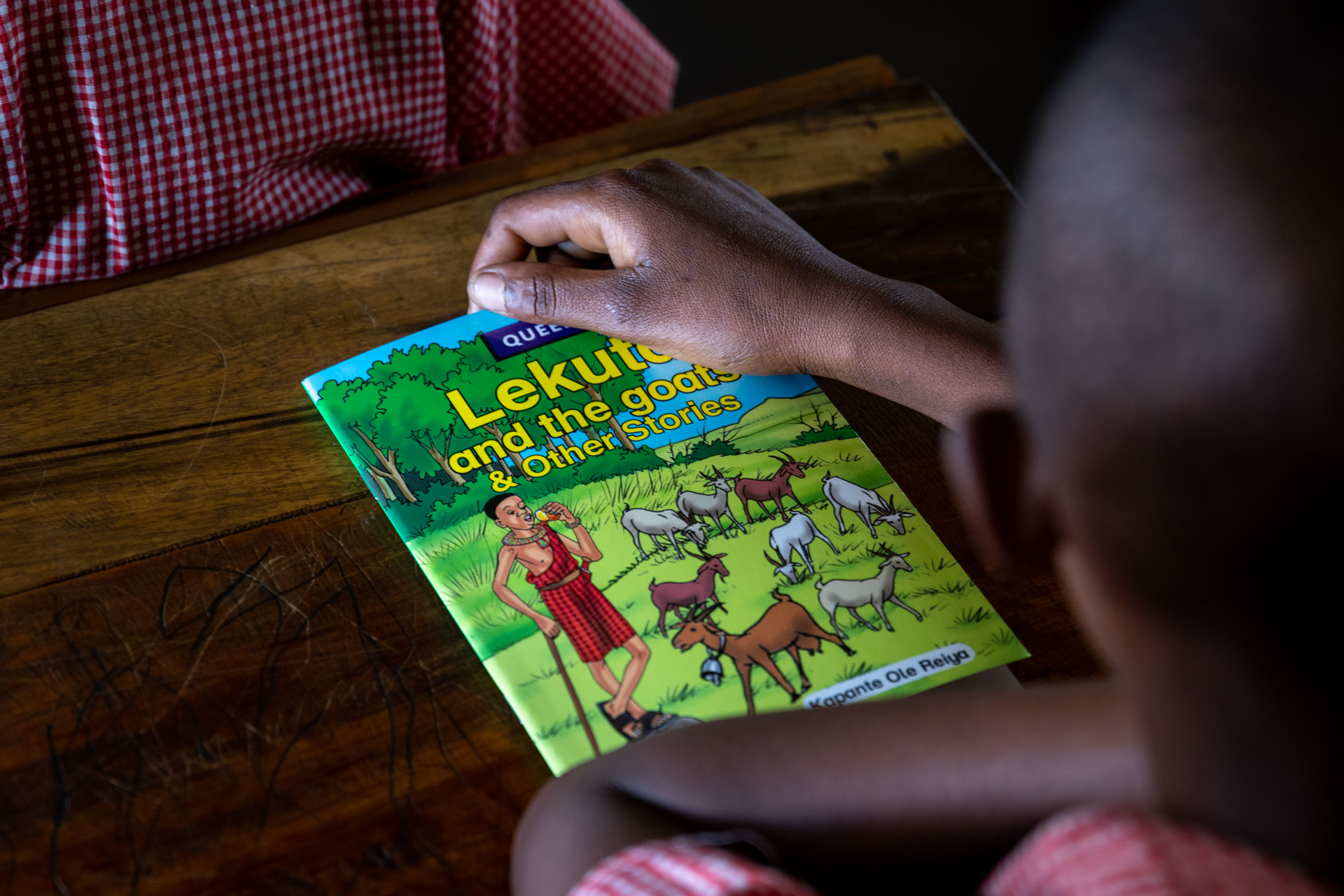

After graduating in 2016, I was employed as a Nation Media Group journalist in the Trans Mara for a year. Then, from the barrel of my pen, came ‘Lekuta and The Goats and Other Stories’ a children’s anthology. Luckily for me, the book was an success selling 6,000 copies in three years.

Writers often explore identity issues in their works. Born and brought up near the Maasai Mara Game Reserve, I’m intertwined with the story of its successes and challenges. Wildlife feed from the same lands as our herds and drink from the same water source. Many Maasai families have leased their lands to conservancies which protect the rich abundance of wildlife in the Mara. This creates a symbiotic relationship.

Threats to this delicate equilibrium were what drove me to write. A case in point is that of Nyakweri Forest, an indigenous forest next to which I live that has long acted as a birthing ground for elephants but is currently facing its last stand. Saviours of the Mara, the 2nd story in the collection sheds light on the intricacies of destruction and safeguarding of this vital resource. It is the story of two young primary school boys, Saruni and Kayia, whose wildlife club leads efforts to preserve the environment and are rewarded for it.

Recently, I went on a book tour of 5 schools in my neighbouring communities sponsored by the Angama Foundation. The goal was to raise a generation of lifelong readers. Education has proved to be a powerful tool empowering our Maasai community to find sustainable solutions to its challenges in line with the World Tourism Organisation’s ST-EP (Sustainable Tourism Eliminating Poverty) goals.

For example, a literate population would put more emphasis on cattle quality and not numbers thus helping in both herd and rangeland management. Job creation, improvement in health and education would channel the socio-economic benefits of tourism. This would also incentivize them to share their home with wildlife.

My maxim always has been that our millennial generation will not be the ones to tell our children that elephants, lions or any other iconic animal in the Mara became extinct under our watch. Two other books, a novella and a second story anthology with animal characters, are in the pipeline.

Filed under: Giving Back

Subscribe for Weekly Stories

Comments (0):

Hot-air Ballooning