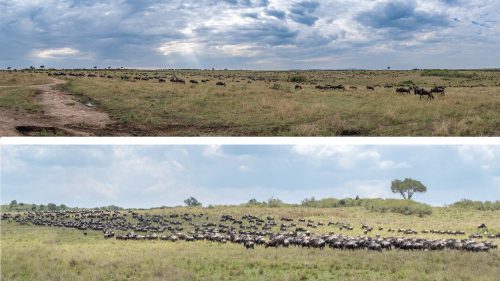

If you thought we were done with the Migration, think again. The third wave of the Great Migration is happening, rather bizarrely, in early October. The last two weeks of rain in the Triangle and the Greater Mara has completely changed the dynamics of the Migration, altering the normal seasonal movements of the herds of wildebeest and zebra.

For the last couple of days, herds of trotting wildebeest have been crossing the Sand River towards the Greater Reserve from Tanzania, eventually crossing into the Mara Triangle. More herds — numbering in the tens of thousands — have been seen heading northwards to the Triangle, so we expect the action to unfold in the coming days.

As always, the wildebeests are often met by predators as they cross. We spotted a mating pair of lions lazily cooling off under some shade on the edge of the river a short distance from a herd contemplating crossing. Suddenly, the female lion seemed interested and started approaching the busily feeding wildebeest herd, staying low to avoid detection. Excitement filled the vehicle as everyone manoeuvred to find a good vantage point. All of a sudden, to our surprise, the wildebeests became alert as alarm calls echoed everywhere. Behold — the king of the jungle was approaching without even the slightest attempt to disguise himself. He was interested in only one thing: mating. She expressed her obvious disappointment by snarling at him.

The welcome and much-needed rains can pose a challenge to some species in the Triangle, like elephant calves who always struggle to walk on slippery terrain. The biggest risk though is faced by animals living in burrows. For example, snakes that normally live underground have to relocate to drier and higher ground as the soil becomes saturated. Generally, snakes emerge when there is rain in order to hunt as rodents and small amphibians leave their homes too. We came across these visibly startled herons making a loud racket and knew it had to be what we like to refer to as a “danger noodle”. And quite rightly so, it was a puff adder.

It’s always thrilling to see a leopard, and in this case, it was a mum and her cub of about three or four months, believed to have crossed from the Greater Reserve to the Triangle up in a tree. She was very shy and a few minutes after our arrival the mother came down and hid in the ravine. Smartly, the cub didn’t as we had spotted some opportunistic hyenas loitering around obviously attracted by the smell of a baby topi kill the leopardess had stashed up the tree.

Do elands have designated babysitters? Just down the Oloololo Escarpment, you’ll find a herd of eland consisting of a large bull with several females. A few metres from the herd, we noticed there was one female with all the calves, always alert and constantly on the lookout for danger. Although calves of these species form a nursery a short distance from the herd where they interact and play together, the one female with them separated from the rest got us thinking. Social interaction, communication, and forms of attachment occur in species other than our own, but it’s not necessarily correct to assume that any of those behaviours is the same in every species. However, clearly, from the photograph, it begs the question again, do elands have babysitters? Our guide Wilson Naitoi seems to think so.

We then stumbled upon Mama Kali, the dominant female of the Angama Pride along with four other lionesses. She was on high alert, scanning the open plains for her next meal. Watching her is always a delight; she walks so confidently, poised and with seemingly unshakeable confidence. A few zebras in the distance caught her attention — shortly after she raised her ears. We had all the cues of a potential hunt. Without further ado, our guide Wilson drove up to the zebras and positioned us perfectly.

From a distance, we watched her slowly approach her target until she disappeared into the long grass. I quickly switched my camera settings, anticipating a dramatic chase. I’ve learnt the hard way that in wildlife photography, failing to prepare is preparing to fail. I sat there, all set to ‘get the shot’. The other four lionesses took their positions, keeping an eye on each other, sending signals and coordinating for the chase. The scene was set, they were almost in striking range. Then, an inexperienced lioness charged prematurely, alerting the zebras and giving them enough time to get away. It was a bit disheartening for all of us that their efforts culminated in a failed hunt, but such is the way of the wild.

Exactly one year ago the Mara was even more centre stage than usual as some of Kenya's budding and established natural history filmmakers came for the Kenyan chapter of the Jackson Wild Summit.

Filed under: This Week at Angama

Subscribe for Weekly Stories

Comments (0):

Weddings in the Mara