The Maasai Mara is exceptional for a number of reasons, not the least of which is its impressive diversity and density of wildlife. But, as any visitor to the Mara will well know, it’s no zoo – there are no fences keeping the animals “in bounds.” This means the relatively dense (and ever-growing) human population surrounding the reserve must co-exist with the park’s megafauna – including those which are potentially dangerous.

This leads to what is known as “human-wildlife conflict,” sometimes abbreviated HWC – and the communities surrounding Angama, immediately adjacent the reserve, are very familiar with it. HWC can come in many forms, from an annoyance like baboons stealing unattended food, to something much more serious like lions killing livestock, which are the Maasai people’s livelihood.

In the latter case, the Angama Foundation has been supporting the Mara Conservancy’s compensation program by subsidising the majority of payments for livestock lost to predators within the area – usually surpassing $20,000 per year. This program helps alleviate some of the tension local communities feel towards predators and hopefully prevents any retaliatory measures.

Recently, the Mara Predator Conservation Programme (MPCP) approached the Angama Foundation with a proposal to try and better understand how and when these livestock predation events happen, with the intention that more understanding and knowledge will inform stakeholders how to prevent such incidents before they occur. The proposal involved collaring two lions in the Mara Triangle that would potentially pose threats to livestock: a female in a pride whose territory is at the edge of the reserve, and a young male soon to disperse from his pride.

The Angama Foundation was happy to provide the funding necessary to purchase two collars for the MPCP to deploy on lions that may be, or have the potential to be, culprits of livestock predation in the communities surrounding us. By better understanding their movements we would find ourselves with a win-win: not only would fewer livelihoods be negatively affected, but the Angama Foundation could redirect compensation funds to other projects benefitting the community. Like with an illness, isn’t it better to prevent it, than to treat the symptoms?

When we received an invitation from MPCP’s Senior Program Scientist, Niels Mogenson, to join a collaring mission this past September, we eagerly accepted – besides doing our due diligence and following up on the projects we support, this was a unique opportunity to observe conservation in action. We set off early in two vehicles to try and locate the target individual: a female within the Angama Pride, whom we know scales the Oloololo Escarpment from time to time to hunt the plateau.

Luck was on our side – we found the pride in relatively short order, in an area below Angama called Shieni, and tracked them while we waited for the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) vet team and representatives from the Mara Conservancy to join us. Dr. Limo, the Mara’s longtime KWS vet, arrived in his customized Sheldrick Wildlife Trust-sponsored Landcruiser with imposing dart gun slung in arm, followed in another vehicle by the Mara Conservancy’s Chief Warden, Alfred Bett, and Administrator, David Aruasa. After a quick brief confirming which lioness of the pride was the target, the team was set.

We watched from about fifty meters away as the muzzle of the dart gun slid out the side of the KWS vehicle. Seconds later a loud PFFT! was followed by a confused and angry growl, the lioness springing up and bounding away with what looked like a highlighter-pink flower sprouting from her haunch. She stopped after about thirty meters, looked around for whatever had stung her bum and, over the course of about fifteen minutes, slowly lay down with head on paws, drifting off into a deep sleep.

Then the team went to work.

Between the MPCP team and the KWS vets, there was a bustle of respectfully quiet activity: removal of the fluorescent feather-tipped dart, application of antiseptic spray to the dart site, blood sampling, tissue sampling, biometric measurements, sizing and fixing of the collar, a general check-up that revealed a couple small wounds and subsequent application of more green antiseptic spray– even the removal of a few ticks.

It was an impressive example of respectful collaboration in an effort to both care for the animal and prepare it for its involuntary procurement of data valuable to conservation research. For those of us observing, it was also a unique opportunity to experience a wild lion up close: marveling at her claws and teeth, admiring her coarse tawny pelage, and just awe of being in such close proximity with an icon of the African bush.

Once the team was done, we hurried away to our respective vehicles while the lioness was administered with a sedation reversal. After a short time, she somewhat drunkenly stumbled to her feet and slunk away, no doubt wondering what had just happened, but otherwise unencumbered by her new necklace.

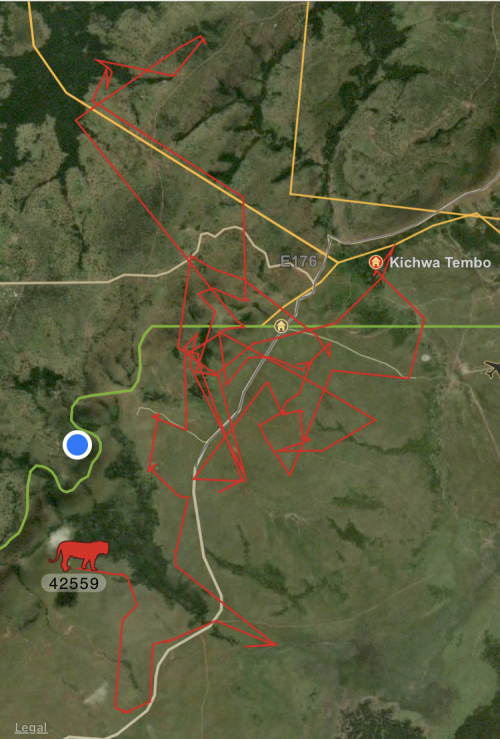

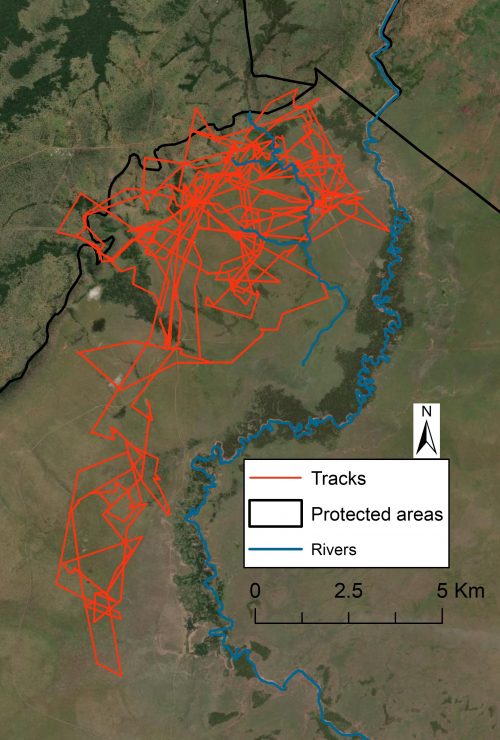

In the months since she’s been collared, Mama Kali (as we now affectionately call her) has both thrived with her pride and already provided some fascinating data. Niels from MPCP has shared with us a summary of her movements on a monthly basis, revealing she ranges far more widely than we originally thought, including overlapping significantly with other prides to the north and south, while also wandering remarkably far outside of the reserve at times. That said, her core home territory is still quite clearly immediately below Angama, which of course we readily welcome. MPCP is still learning from the data and we’re eager to see the ways they can use it prevent future conflicts.

As Mama Kali continues to do as lions do, let us not forget to thank her for her unwitting participation in informing local conservation policies and preventing further human-wildlife conflict. Thank you, Mama Kali!

Filed under: The Mara

Subscribe for Weekly Stories

Comments (0):

Angama Image Gallery