We were recently inspired to be a bit more curious about the names attributed to places and wildlife in East Africa, and more importantly the people behind those names, when Nicky’s brother, Peter, discovered a statue of Joseph Thomson in Thornhill, Scotland, accompanied by a plaque that commemorated him for his expedition through “Maasai Land” (among elsewhere in East Africa).

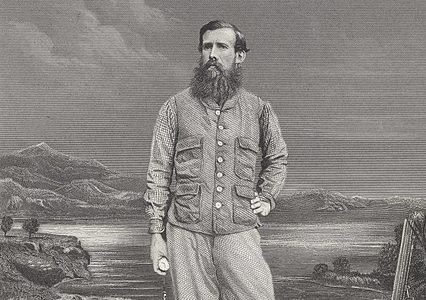

Peter has again inspired us to continue this series of “What’s in a Name?” when he shared with us that not far from his home in London, another revered British explorer is buried: Sir Richard Francis Burton.

Unfortunately for Sir Burton, his is not a name you’ll come across on an East African safari, lest someone is talking about history. No iconic location or charismatic megafauna, no bird, insect, flower, grass, or even microscopic fungus is named after him. Regrettably, this makes him somewhat of a poor subject for this series, as he was undeniably an interesting man.

What Sir Burton is famous for, however, is his rivalry with John Hanning Speke who, although lacking Burton’s honorific “Sir,” does have several animals named after him: two gazelles, two reptiles, and a bird. Four of these can be found in Kenya, and one you have a likelihood of encountering on a safari from Angama (or perhaps from a nearby safari camp called “Speke’s Camp”) a member of the iconic and charming weaverbird family, the beautiful Speke’s Weaver.

As briefly summarized in an entry from a fantastic book called “Whose Bird?” Speke was actually a co-leader with Burton in two separate expeditions, both funded by the Royal Geographic Society, and was initially less interested in the expedition itself than he was in hunting big game. Interestingly, relying on each other for survival during these expeditions, itdidn’t prevent Speke and Burton from eventually becoming sworn enemies.

It was during the second expedition (the first failed catastrophically when 200 Somali warriors attacked their camp, with Speke suffering eleven separate wounds, including a spear through his thigh, and Burton being impaled by a javelin through both his cheeks), that Speke became obsessed with finding the source of the Nile and focused his efforts on this pursuit – perhaps in competition with Burton, as the two had quickly and increasingly fostered an intense dislike for one another.

Both Burton and Speke were plagued by illnesses, often critically so, during this expedition. Upon reaching Lake Tanganyika, Speke was actually too blind (temporarily) to see it. Later, Burton was too weakened to continue traveling, a fortuitous turn of events for Speke, who continued on alone to become the first European to see Lake Victoria. This “discovery” of Lake Victoria spawned Speke’s theory that he had also discovered the source of the Nile.

The rift between Burton and Speke grew rapidly from this point forward, as jealousies led to arguments and accusations, with Burton ultimately not only denying with vehemence Speke’s theory, but using considerable time and energy to discredit him. This was probably exacerbated by Speke being chosen by the RGS to lead a second expedition in 1860 in search of the source of the Nile (with co-leader James Augustus Grant, for whom the Grant’s Gazelle is named), the result of which was a celebrated success that Burton had to watch from the sidelines.

Burton and Speke’s rivalry continued to intensify, often spurred by the media, as both continued to discredit the other, each with success (ironically and sadly to the detriment of their true successes as explorers). Finally, in 1864, the widely publicized conflict was headed for a dramatic conclusion as both were scheduled to have an in-person debate over the source of the Nile in front of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Tragically, in an effort to release some of the pre-debate pressure and tension the day beforehand, Speke accidentally shot and killed himself with his own hunting shotgun as he scaled a brick wall.

As we all now know, it was Speke who was correct and Burton who was wrong, though at the time the enmity was so strong that Burton continued to deride Speke and his theory, even openly suggesting that Speke’s death was a suicide because he so strongly feared the debate. Perhaps it was Burton’s tasteless handling of the end to the drama, and Speke’s ultimate victory, that played a role in Burton’s name largely absent from present-day East Africa, while Speke’s legacy lives on in five vertebrates and a camp in the Maasai Mara.

Filed under: East Africa Travel

Subscribe for Weekly Stories

Comments (0):

Angama Safari Camp