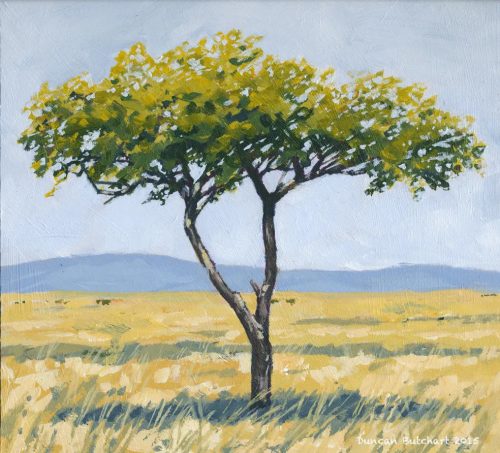

In Swahili, the word ‘mara’ means ‘spotted land’ – and when you are flying above the Maasai Mara in a small aircraft or gazing out across the plains from Angama Mara lodge, it’s easy to see why. Like the coat of a cheetah, the grassland is dotted with hundreds of thorn trees, widely spaced, their crowns far from touching. These are not acacias, but the so-called ‘Desert Date’ – better known by their botanical name Balanites aegyptiaca.

This hardy, evergreen tree occurs over much of Africa and parts of the Middle East, and is able to grow in many different soil types, including the heavy clays of the Mara Triangle. One thing that is apparent to anyone who drives or walks among these trees, is that there are no young ones, no saplings, only old, gnarled individuals, standing up to 10 to 12 metres, their lower branchlets constantly clipped by browsing giraffe and elephants. As all of the Desert Dates are about the same size and have the same girth of trunk they must be more-or-less the same age. This is a fairly slow-growing tree, with hard timber valued by the Maasai for spear and knife handles, and carved into four legged stools.

The absence of young Balanites trees tells a story. It is a story of cycles. Cycles of elephants, cycles of fire. Today, the seeds of Balanites that germinate in the Mara will grow into tiny saplings sprouting in the grass, but they will be browsed right back by herbivores before they enter their second year. And those are the exceptions – most are turned to ash by the seasonal grass fires. With their thick, dark bark, the adult trees can withstand the fires, but the young plants are defenceless. This tells us that fire was absent when the trees we see today developed through their vulnerable stage (at least 20 years, or so). For that to have been the case, the Mara must have been a closed-woodland habitat, too shady for grass. There would have been no wildebeest or zebra back then. Then, what surely happened, was an increase in the elephant population. Perhaps large numbers of the pachyderms moved into this part of Kenya due to ivory-hunting pressure elsewhere, we’ll never really know. These elephants – the gardeners of the savannah – simply chomped up the woodland, thinning it out so that grass was able to flourish in sunlit clearings. These clearings became larger, and fires flared. Perhaps there were other species of trees, acacias maybe, growing in the woodlands but only the strong and sturdy adult Balanites could withstand both elephants and fire.

At any rate, these survivors still stand and make the Mara what it is. The crown of each Balanites tree creates a pool of shade for lion, cheetah, topi, wildebeest and zebra. Lazy leopards languish on the limbs, technicolour agamas scuttle up the trunks, vultures build nests on their canopies . . . and the world keeps spinning.

Filed under: The Mara

Subscribe for Weekly Stories

Comments (5):

14 September 2021

It really fantastic

24 December 2015

Lovely article about a place I adore. Very well written.

29 December 2015

thanks Lillian !

24 December 2015

Often wondered why we only see mature trees in these open grasslands. Great writing as always.

29 December 2015

thanks Graeme!

Out of Africa