Last year, on a trip to a remote stretch of northern-western Namibia, we had the opportunity to meet the fascinating Himba people. You’ve likely seen the photos of them: the women painted head to toe in red-orange clay, adorned with jewellery, covered only from the waist down in animal pelts. Like most travellers, we jumped at the chance to witness a culture so unique and different to our own, a way of life unchanged over centuries.

As we approached their “village” it became apparent this was not their home. They had driven a white pickup truck, stashed behind a far-off tree, to a collection of huts meant to simulate their village. We mingled around not knowing what to do, as one of the women demonstrated how they apply the ‘otjize’ (a mixture of butterfat, ash and ochre) to their skin and another lit a fire of incense meant to cleanse and deodorise the body, while the others minded some of the babies in their midst. Eventually, they ushered us over to their stand filled with bracelets and figurines, waiting for us to buy something. The women felt distant and uninterested, on show. We left feeling terribly guilty.

So when, on a recent trip to Botswana’s Mgkadikadi salt pans, we were told we would be having a San people’s ‘Bushman’ experience I was leery. How were these people being treated? Would it be a humane experience? How would I — and more importantly, they — feel about it after?

When we arrived, there were a few traditional huts set amongst some trees, built to demonstrate their homes; I started having flashbacks. There were several members of this tribe, nearly 20, and two of the young men who spoke English were quite jovial in nature which helped put us at ease. They introduced everyone by name and explained what would happen: we would walk with them, stopping along the way to explain some of the ways they navigate the land and encouraged us to ask questions and take pictures.

As we walked, I asked if they were related and if this was their home. He explained that they were uncles, aunties, cousins, but their home village was actually a few hundred kilometres away and that they were employed in shifts. The lodge operator had built them a traditional village nearby so that they would be comfortable when 'on duty', then after several weeks, they would return home and another family from the village would take over. He seemed pleased with that; I suppose if you’re going to be employed this way, that’s the best outcome.

After a few metres trek, they stopped and pointed to a tree, explaining it was necessary for hunting (a practice now banned in Botswana — a win for conservation but a harsh reality for them — needing to find new a way to sustain themselves: enter eco-tourism). Turns out there is a type of leaf beetle that lays its eggs on this particular tree and when the larvae hatch, it produces a liquid that is poisonous — an evolutionary defence mechanism to help protect them from predators, no doubt. The San people would then collect the sap that had fallen at the bottom of the tree and use it to poison the ends of their arrows.

Two of the young men peeled off into a field and started digging feverishly. As we followed curiously, one declared ‘We are hunting for scorpions’. Not how I expected to spend my afternoon. As they chopped at the ground with their sticks, one explained that this was a childhood pastime — that scorpions have networks of channels just beneath your feet and following them will lead you to a scorpion. Sceptical to say the least, I watched as one continued to follow a seemingly imaginary tunnel until a yellow scorpion magically appeared.

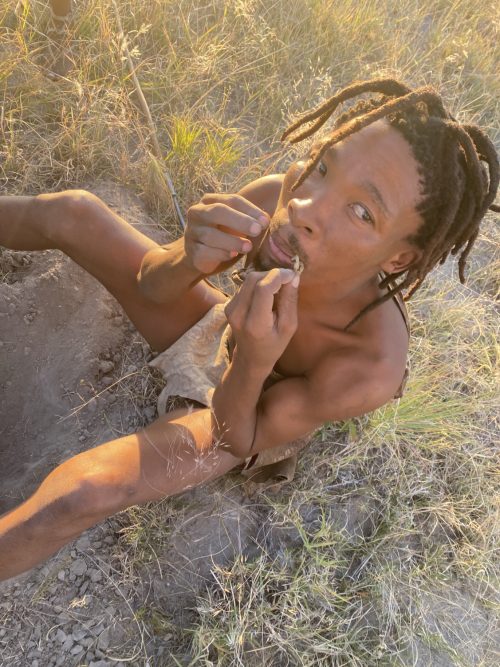

Holding it by the stinger he proceeded to show it off to us, then placed it in the palm of his hand, playfully demonstrating its defensive position. Grabbing the scorpion again — one hand on the stinger, the other on the pincers — and with a wide grin, he told us was going to ‘give it a bath'. He then put the entire torso in his mouth and gave it a wash with his tongue(!). As we watched in astonishment, he eventually took it out and told us that it was calming to the scorpion, placing it back in the palm of his hand where it was totally docile. (I do not want to know how they discovered this worked and any failed attempts at it).

He insisted we each hold it in our hands and that we would be totally fine. Not wanting to be the one who needed to be airlifted out of the bush I was ready to decline, but after it made the rounds I caved to peer pressure and managed to live to write this blog for you, Dear reader. Not sure what would happen to the scorpion after being caught, I was surprised and relieved to hear them say it was time to put it back — as they dug a new tunnel, gently placed it in the ground, and covered it with soil. It would have been easy for them to kill it for sport or fling it away. That small act of respect for nature had me reflecting on all the horrible ways we treat insects as children.

We next joined the rest of the tribe who had started to demonstrate how they make fire, quickly rubbing a stick into another stick, placed on the bottom side of a leather sandal with crushed dried grass as a tinder. It was a display of teamwork, a constant relay race of men starting at the top, taking turns rubbing the stick between their hands down towards the bottom and going back to the top of the line. After the fire started, they declared it was time for a game — a San version of rock, paper, scissors. There were two teams of three, and one of the elder females was drafted to play (I suspect she was a bit of a sniper). Those not playing sat encircling them, participating by chanting and clapping while the players added their own emphatic sounds to their wind-up and 'throw' of their hand. I was enthralled — the entire group was engaged, joined in song, cheering players who won a hand and playfully jeering those who lost.

Even though I didn’t quite understand the rules and couldn’t tell who was winning or losing, it didn’t matter. I recognised the scene, knew this type of kinship and laughter and was instantly filled with gratitude that they had shared theirs with me. And that's when I knew they had gotten this cultural interaction right.

Filed under: Stories from Angama

Subscribe for Weekly Stories

Comments (0):

Angama Image Gallery